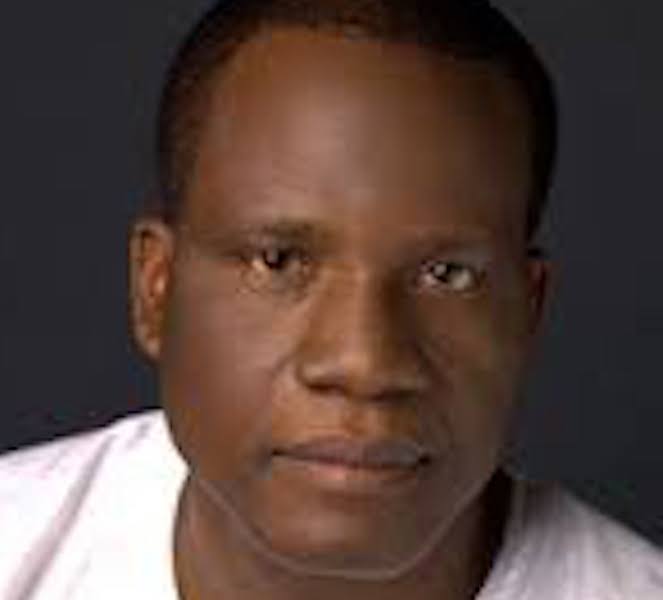

BY KAYODE KOMOLAFE

KAYODE.KOMOLAFE@THISDAYLIVE.COM

0805 500 1974

It was an opportune time in Benin two days ago to reflect again on the long-standing issues of Nigerian federalism. The occasion was a conference organized by the Edo State government to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the creation of the old Midwest region, from which the present Edo and Delta states have emerged.

Rich tributes were held to the memory of the leaders who pioneered the struggle for the creation of the region. These historical figures included the first prime minister of the region, Sir Denis Osadebay, Oba Eweka II, Oba Akenzua II and the great nationalist, Chief Anthony Enahoro. Under the theme, “60 years after the referendum, what is the Midwest?”, speakers at the forum looked back on history as they expressed hope for the future.

The arrival of the Midwest in the Nigerian federal landscape was remarkable in many respects.

On July 13, 1963 the federal government held a referendum to determine the wishes of the people of the Midwest on the question of carving the area out of the old Western District. The western region stretched from Badagry in present day Lagos State to Patani in present day Delta state. Almost 90% of the people voted in favor of the creation of the new region as the fourth in the Nigerian federation at the time. Over the past 60 years, more states have been created by successive military regimes. The four-region structure of 1963 is today a federation of 36 states. However, the agitation for more states has hardly subsided.

However, as a former governor of Edo State, Prof. Oserheimen Osunbor put it in his goodwill message at the forum, because of its democratic content, the history of the creation of the Midwest Region should be read in a fundamentally different way than that of its creation of any other state. The Midwest was the only geopolitical unit created based on the will of the people expressed in a popular referendum. According to Osunbor, just as the colonialists never considered the people in the formation of Nigeria, military regimes created states by decree. As opposed to the use of force, the Midwest emerged from political negotiation and mobilization. Yes, there were maneuvers along the way!. For example, the Prime Minister himself, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, promoted the referendum motion in the Federal Parliament. Undoubtedly, a lot of politics played into the process, as will be seen later in this column. But it was all legal. After all, as another scholar puts it, what is federalism if not a perpetual negotiation? The mere fact that two regions emerged from the one region created 60 years ago is proof that political maneuvering in a federation is endless. Perhaps, more than any other point, it is the democratic origins of the Midwestern region that has set it apart from the states that have come into existence since.

The standard case for state creation was that this exercise in political engineering would bring development closer to the people. The chief host of the forum and Governor of Edo State, Mr. Godwin Obaseki, provided a yardstick to measure how much the dream has been realised. Obaseki aptly put it this way: “Sixty years after the referendum, we are still grappling with numerous socio-economic challenges, which require the restoration of the institutions and structures that supported the region in the past.

“This is why we have undertaken holistic reforms of our institutions in Edo State in the last seven years. We have made reforms and innovations in various sectors of the economy that have opened up Edo for investment.

“We must continue to work together to overcome challenges, build on our successes and maintain partnerships towards building a strong and masculine region.”

The theoretical background for the discussions was set by the director-general of the Institute of International Relations, Professor Eghosa Osaghae, focusing on the idea of ”federal solutions” to the problems of federalism. State creation is a solution of form. Other forms of federal solutions include decentralization and decentralization. For some, it could be the ultimate breakup. The political scientist paraphrased a famous authority on federalism, Sir Kenneth Clinton Wheare, saying that textbook prescriptions for federalism should only be used as guides because federalism would practically evolve according to the realities of a particular state. Enthusiasts of the federalist option often call for “true federalism.” But as Osaghae reminded the forum, each nation would practice federalism according to its political, historical and cultural particularities. American federalism is not identical to Indian federalism. Nor is Australian federalism identical to Canadian federalism. So instead of pursuing the specter of a “true federalism”, genuine federalists should be more creative in making Nigerian federalism workable. In Osaghae's view, Nigerian federalism has evolved as a result of the aggregation of federalist principles. Referring to the 1963 referendum as a “negotiated solution” by a people ready for self-determination, he distinguished between “regional-centric” and “nation-centric” approaches.

Other speakers drew on Osaghae's eloquent formulation. Another keynote speaker, Professor Edward Erhagbe seized on the imperative of “fiscal federalism” and the revision of the legislative roll to give more powers to the state. A radical scholar, Professor Godini Darah, unequivocally called for “resource control” as the solution to the fundamental problems of Nigerian federalism. Dara argued that Nigeria should rather return to the 1963 Constitution in the same tone as the elder statesman, Chief Edwin Clarke. Nigeria's former ambassador to Ethiopia, Mrs. Nkoyo Toyo, and former member of the House of Representatives has identified the oppression of “small minorities” within a minority group. The contradiction between a minority group and a small minority within it is often overshadowed by the larger contradiction between the minority group and a majority group. This trend is worth pondering because the issues of Nigerian federalism are not only geographical. ethnic bases are very strong.

Ambassador Godknows Igali, who moderated the conference, drew the audience's attention to the “elite consensus” evident in the politics of creating the Midwest region. For him, a pan-Nigerian approach would be necessary to solve the problems of Nigerian federalism. He challenged the former governor of Edo State and now a senator, Comrade Adams Oshiomhole, to give an account of how members of the National Assembly from the South-South are forging elite consensus to solve the region's problems. Oshiomhole commended his successor, Obaseki, for fittingly organizing the forum to reflect on the journey of the Midwest in 60 years and Edo State in the last 32 years since its birth. He said senators from different parties representing the three constituencies of Edo State in the Senate are pushing for the rehabilitation of federal roads in the state. In his first days in the Senate, Oshiomhole moved a motion in the dilapidated Benin-Auchi state road that also links Edo state to Kogi state. Oshiomhole also called for the revival of the regional development block concept for the South-South states of Bayelsa (B), Rivers (R), Akwa Ibom (A), Cross River (C), Edo (E) and Delta (D ) – BRACED. According to him, the properly organized BRACED Commission could promote joint development efforts that could make the South-South states a stronger bloc. Well, politicians usually focus more on states as federal units and less on economic regional blocs. Oshiomhole also made an observation worth pondering for those who still call for the creation of more states than the existing 36: the more the federal units evaporate, the weaker they become vis-à-vis the centre.

The element of “elite consensus” that Igali proposed would be critical to achieving federalism as famously defined by KC Wheare: “the method of dividing power so that the general and regional governments are each in a coordinated and independent sphere ».

One aspect of the Midwest's history that was not emphasized enough at the symposium was that elite consensus was not easily forged in the creation of the fourth region. Balewa was excited to move the motion for the referendum of 1963. But the Prime Minister himself was not willing to support the creation of the Middle Belt region that Joseph Tarka and other regional leaders had valiantly fought for. The leaders of the Middle Zone also wanted to be out of the Northern Region. The party of Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, the National Council of Nigerian Citizen (NCNC) was at the center of the demand for the creation of the Midwest Region and Osadebay, who emerged as the premier of the region, was the leader of the NCNC. The NCNC did not support the creation of Calabar-River-Ogoja (COR) state out of the Eastern Region. Chief Obafemi Awolowo, the first prime minister of the old western region, has been in custody and on trial for treason since the creation of the Midwest. In principle, Awolowo was not opposed to the creation of the Midwest or any other region for that matter. As early as 1947, Awolowo wrote in his book entitled: “Path to Nigerian Freedom” that the “ultimate aim” of the federal pursuit should be: “Every group, however small, is entitled to the same treatment as any other group, no matter how large… Each group must be autonomous in its internal affairs. Each must have its own Regional Assembly.” This was the position of his party, the Action Group (AG). And under Awolowo's premiership, the Western House of Assembly in 1955 passed a resolution to support the call for the creation of the 'Benin-Delta' state. Benin-Delta State was the original name given to what later became the Midwest Region. Before the resolution, Enahoro, who was also the AG leader, had called for a conference in Chapele to demand a Benin-Delta state.

As Oshiomhole said in his unusually brief goodwill message to the conference, telling the story of the Midwest factor in the evolution of Nigerian federalism is a profound service to history. It was remarkable that a large number of young people were in the audience listening to the various perspectives introduced to the important reflection.

Eminent historian, Professor Jacob Ade-Ajayi, once observed that proceeding on the path of development without a good knowledge of history is like driving a car without mirrors. Undoubtedly, such a journey could be prone to accidents. That is why those policymakers who once removed history from the school curriculum committed an unforgivable error of judgment with their warped view of education. A historical review is important in discussing issues such as state formation, so that all sides of the debate are adequately illuminated.

Overall, 60 years after the creation of the Midwest, the mobilization for statehood has not stopped in parts of the country, including Edo and Delta states. Looking back at history could, therefore, help find federal solutions to Nigeria's geopolitical problems.