At one time, Democrats in the industrial Midwestern state could count on the votes of blue-collar workers, often unionized workers in the many factory and mill towns that dot the region. But according to a new report of democratic strategies that preview in the New York Times, over the past decade, many voters living in strongholds that have lost manufacturing jobs have embraced former President Trump and the Republicans. Now Democrats find themselves in a quandary, facing the prospect of their once-legendary “blue wall” collapsing. What happened? And what should they do about it?

Popular perceptions aside, and as I have written before, today there is no monolithic Midwestern “Rust Belt” of struggling industrial and mill towns. There was once a shared economic history among the small, medium, and large manufacturing communities that crisscrossed the fields, forests, and along the rivers and lakes of the upper Midwest.

But this manufacturing-based economy, shaken by globalization, technological change and new competitors, has undergone decades of restructuring. and in some places the complete disappearance of manufacturing plants and their well-paying jobs. Communities have struggled to adapt.

Today they exist two Midwest — the many former “factory towns” that have made the transition to a new, more diversified economy; and others that have lost their economic anchors and are still struggling.

In today's technology-driven knowledge economy, economic activity tends to be concentrated in major metros, and the Midwest is no exception. In the industrial heartland – from Minneapolis to Indianapolis to Pittsburgh – the major metros have largely turned an economic corner. Likewise, the numerous Midwestern university towns such as Iowa City, Iowa. Madison, Wis.; Ann Arbor, Mich. and State College, Pa., are flourishing.

The same cannot be said for the numerous small and medium-sized industrial communities that characterize the Midwestern economic landscape. Some have developed their economies, but many others have not.

These small and medium-sized factory towns have enormous political influence. In Michigan and Wisconsin, for example, more than half of the voting population resides in the smaller and medium-sized manufacturing communities.

And as the report from strategy papers by Midwestern Democrats Richard Martin, David Wilhelm and Mike Lux, to the communities that have seen the most severe industrial job losses, the ground is fertile for a nationalist, nostalgic and populist appeal like the one offered by Donald Trump.

Why is this? The residents of the struggling industrial communities are responds to messages of leaders who identify with them and against urban elites — leaders who promise to bring back industries that once provided good-paying jobs and blame trade deals and immigrants for their community's ills.

And this populist message can come from the left or the right. Both Donald Trump and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) (who did very well in Midwest factory-town communities in the 2016 primary, beating Hillary Clinton in Michigan) have offered a politics of resentment — essentially a message which says: “You get screwed and someone else gets theirs at your expense.”

But right-wing and left-wing populists differ on solutions. Left-wing populists like Sanders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) offer policy fixes: for example, taxing the rich to provide free college, health care and a higher minimum wage. Right-wing populists like Trump play with identity and terrorize social and cultural issues, with a nod to nationalism and white supremacy, to appeal to voters.

Responding to these cultural cues, many white working-class voters have abandoned the Democrats. And no doubt progressive Democrats (especially those representing districts and states far from middle America) are not helping themselves and further alienating Heartland voters with hardline positions on guns, immigration and abortion.

But the root cause behind the embrace of populist messages is the economic situation and the deterioration of once-thriving working-class communities.

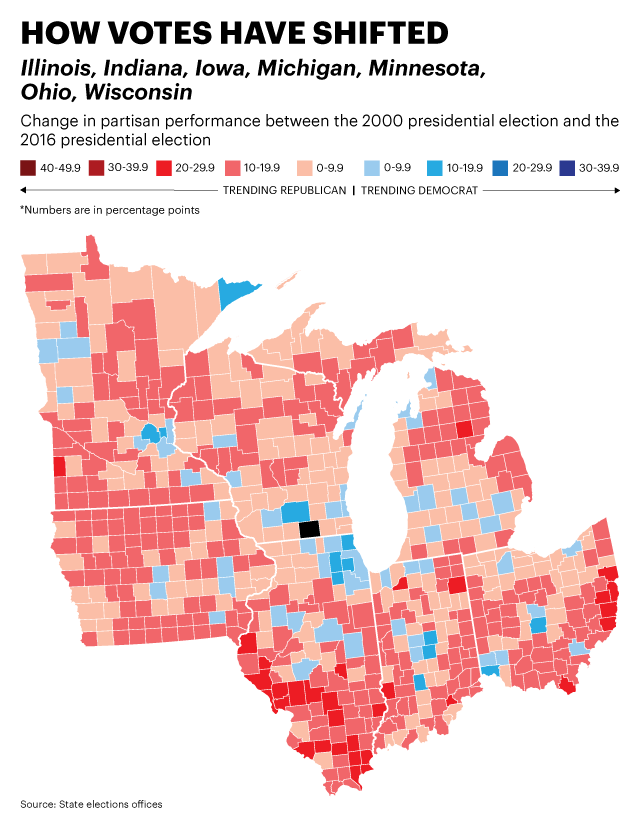

And many of the Midwest's small and medium-sized factory towns are struggling. In 2016 many of these very communities turned to Donald Trump — enough to score electoral victories in the once solidly Democratic states of Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

In the 2018 congressional midterms and 2020 presidential elections, these struggling factory towns he even went “Trumpier.” Democrats narrowly carried this election by winning their most affluent cities and suburbs, including some historically Republican ones.

Now Democrats are sounding the political alarm for 2022 and 2024. report from Democratic strategists warns, in the words of co-author Martin: “if things continue to get worse for us in small and medium-sized working-class communities, we may give up all hope of winning the battleground states of the industrial heartland.”

The report notes that the Midwest mirrors the nation's voting trends, with Democrats gaining votes in recent years in larger cities and their suburbs while losing votes in rural areas. However, according to the report, the biggest losses occurred in small and medium-sized industrial communities that shed manufacturing jobs (and the good health care that comes with them) over the past eight years. More than 2.6 million fewer Democratic votes in 2020 than in 2012 came from once-blue Democratic strongholds like Chippewa Falls, Wis., and Bay City, Mich.

Strategists worry that without Trump's polarizing presence on the ballot (at least in 2022), moderate suburban Republicans, pushed away by Trump, may return to their party. Absent those votes in key Midwest congressional districts, the Democrats' electoral goose may be cooked.

Democrats are right to be concerned. The report makes no recommendations on how to win back those voters. But the agenda for how Democrats do best can be read between the lines.

Exists evidence that when older industrial communities decline, residents are more receptive to the polarizing messages of the right. But there is also strong evidence that where former Rust Belt communities are finding new economic footing, the lure of indignant populism is waning as residents grow more optimistic about the future.

This happened in the case Midwest. Residents of industrialized communities that have made the transition to a new economy exhibit different attitudes and voting patterns than those in communities that are still struggling. Resurgent industrial communities such as Pittsburgh, Pa., and Grand Rapids, Mich., as well as several smaller formerly industrial Midwest communities that have turned an economic corner, see strong trends away from nationalism and nostalgia and toward moderate centrism. This was true of both 2018 Midterm Elections and to Election results November 2020 — when once solidly Republican counties like Kent County, Mich., home to newly booming Grand Rapids, called for both a Democratic governor and President Biden.

Democrats need to focus less energy on infighting and more energy on providing economic opportunity and optimism to predominantly white working-class voters in and around the still-struggling industrial communities of the Midwest. They can begin this effort by refusing to support them or tell them everything that is wrong with their communities. It also includes not telling them they are racist or “deplorable” for voting for Donald Trump.

Democrats need to stop using language that mocks the pride and identity of factory town residents, such as “post-industrial,” or describing residents' hometowns as part of the “Rust Belt.”

What working-class voters want to hear from Democratic leaders is: “We see you. We understand why you are upset with the conditions of your community. You and your community and future success are a national priority. We are here to support you and offer resources to build your own future.”

Only then can Democrats begin to rebuild the blue wall.

John Austin directs the Michigan Economic Center and is a non-resident senior fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and the Brookings Institution.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.