The 2016 US presidential election shocked the world when several dozen counties in the three Midwestern “blue wall” states of Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin – once reliable Democratic strongholds – avoided supporting Democratic President Obama in the previous election and handed Republican Donald Trump, very narrowly, the Presidency.

Earlier that year, Brexit in the United Kingdom saw voters in similar once-reliable Labor strongholds among the industrial regions of the North of England (known there as “Red Wall”) express their disillusionment and drive Britain out of the EE. These seismic events sparked a global struggle to understand what it was that made the voters of the many industrial heartlands struggling in our Western democracies so angry and alienated, and what could be done about it.

Since then we have worked on both document the connection between the economic conditions of the industrial heartlands and support for polarizing, sometimes anti-democratic populist movements (the 'Geography of Discontent' in this EU analysis), and sharing strategies on how to attack the root cause of these grievances: the real and perceived economic decline of once proud and powerful industrial regions.

Then both 2018 Midterm Elections and Presidential election 2020 in the US, we found that residents of those economically cornered industrial heartland communities were less supportive of the extreme rhetoric and policies of the MAGA movement under Trump. In contrast, those industrial communities still experiencing population decline and job losses became increasingly “troubled.”

The 2022 US midterms were another test of this pattern. It was a big relief to many that a group of moderate Republicans and independents in key battleground states strategically voted against the most extreme “election deniers” among Trump supporters—sending their majority to defeat and undermining Trump's potential for further attacks on democracy. But the underlying pattern of Democrats continuing to lose working-class voters, particularly among residents of industrial communities experiencing long-term economic decline, remains.

With the help of students at a Monmouth college Politics and Government in the Midwest Of course one of us teaches every year, we found after the most recent 2022 midterm elections, that the economic and demographic trends in most of these Obama to Trump counties were one of continued decline and political shifts to the right.

The 113 counties in eight Midwestern states that voted twice for Obama and then for Trump in 2016 are still characterized by population loss, declining income, youth flight and low educational attainment. They are also much less diverse than their state counterparts.

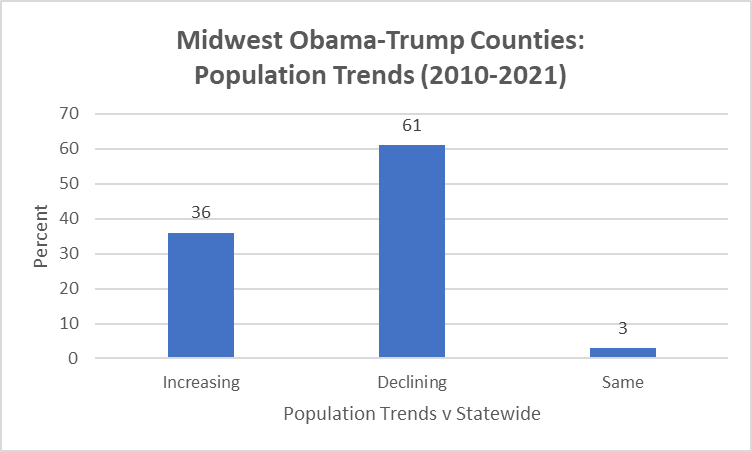

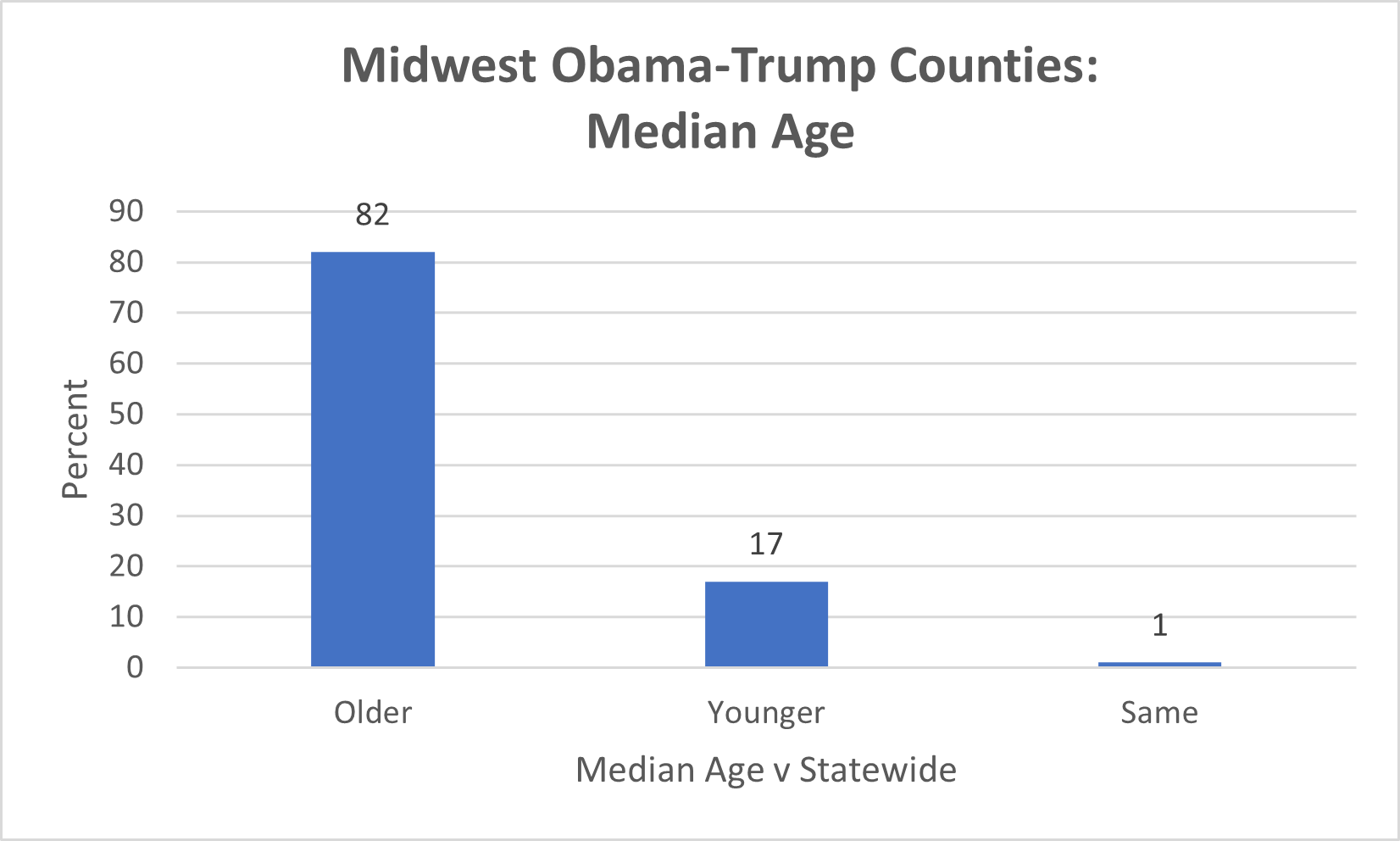

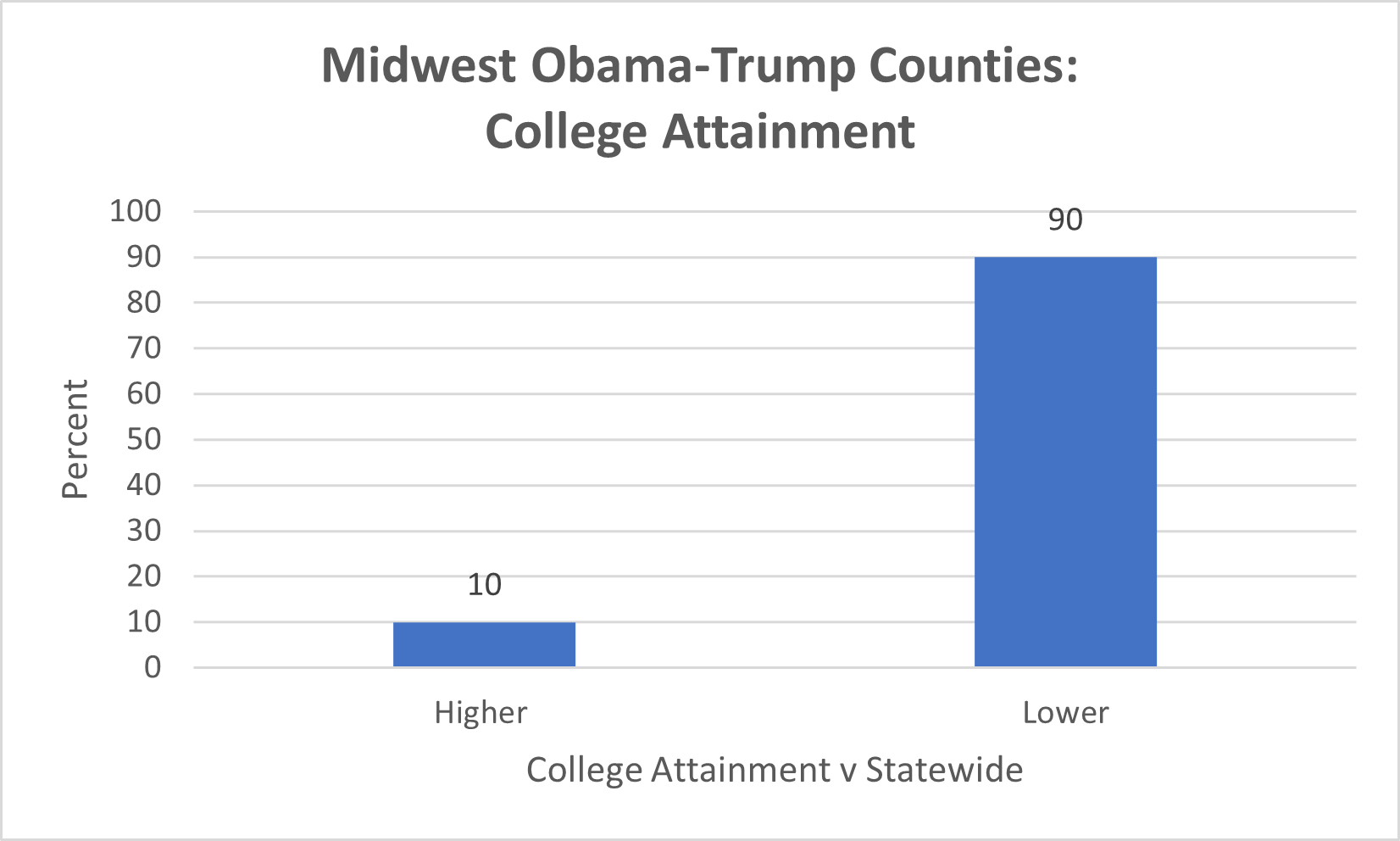

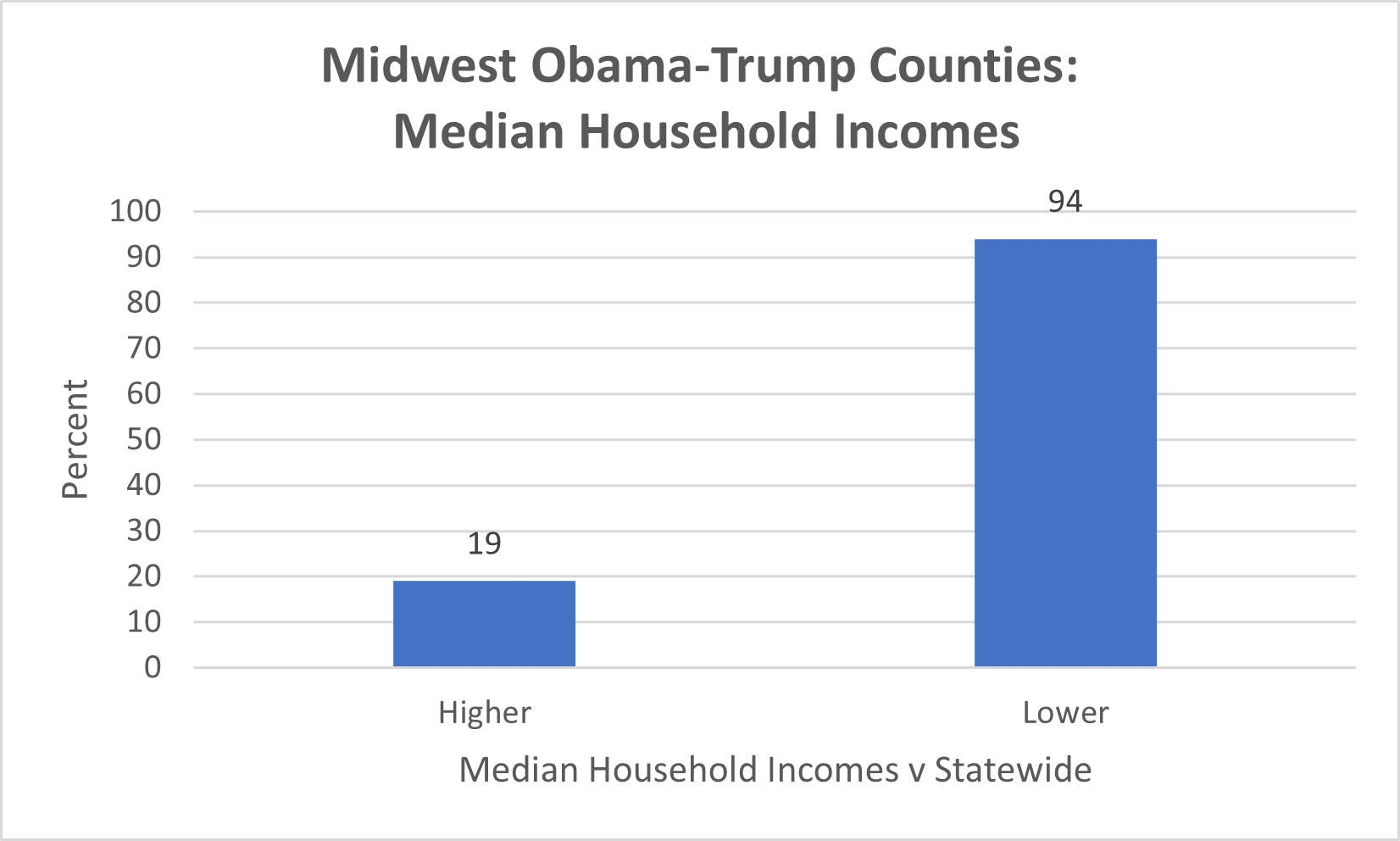

As shown in Figure 1. Of the 113 Obama to Trump counties:

- 93 (a whopping 82 percent) had populations whose median age was higher than their state median age.

- Only eleven of the Obama-to-Trump counties (10 percent) had higher college enrollment than their home states. 102 counties (90 percent) had lower.

- More than 60 percent of Obama-Trump counties saw population declines.

- Of the 113 Obama-to-Trump counties, only 19 had median household incomes higher than their state average, while 94 (83 percent) had incomes below their state average.

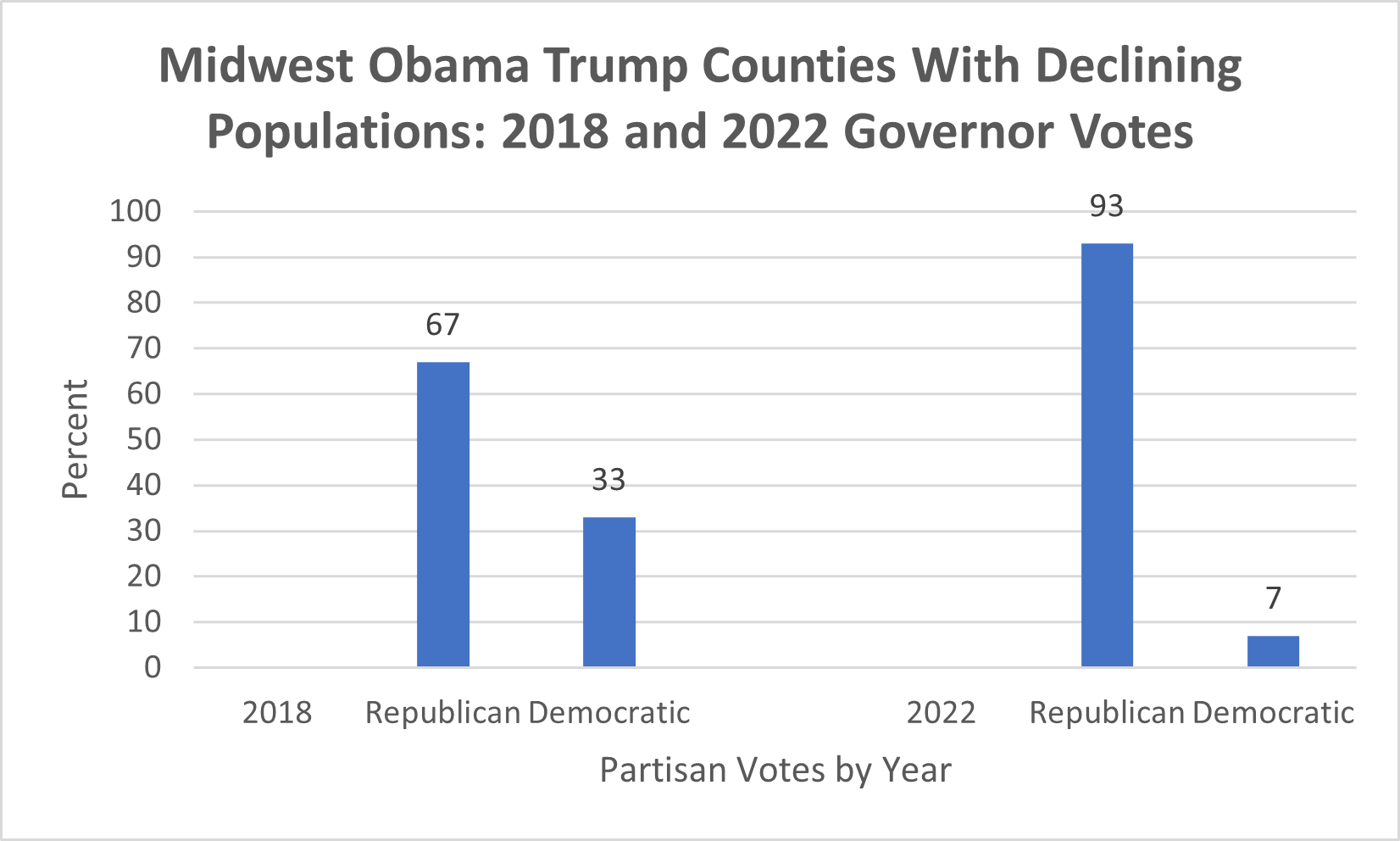

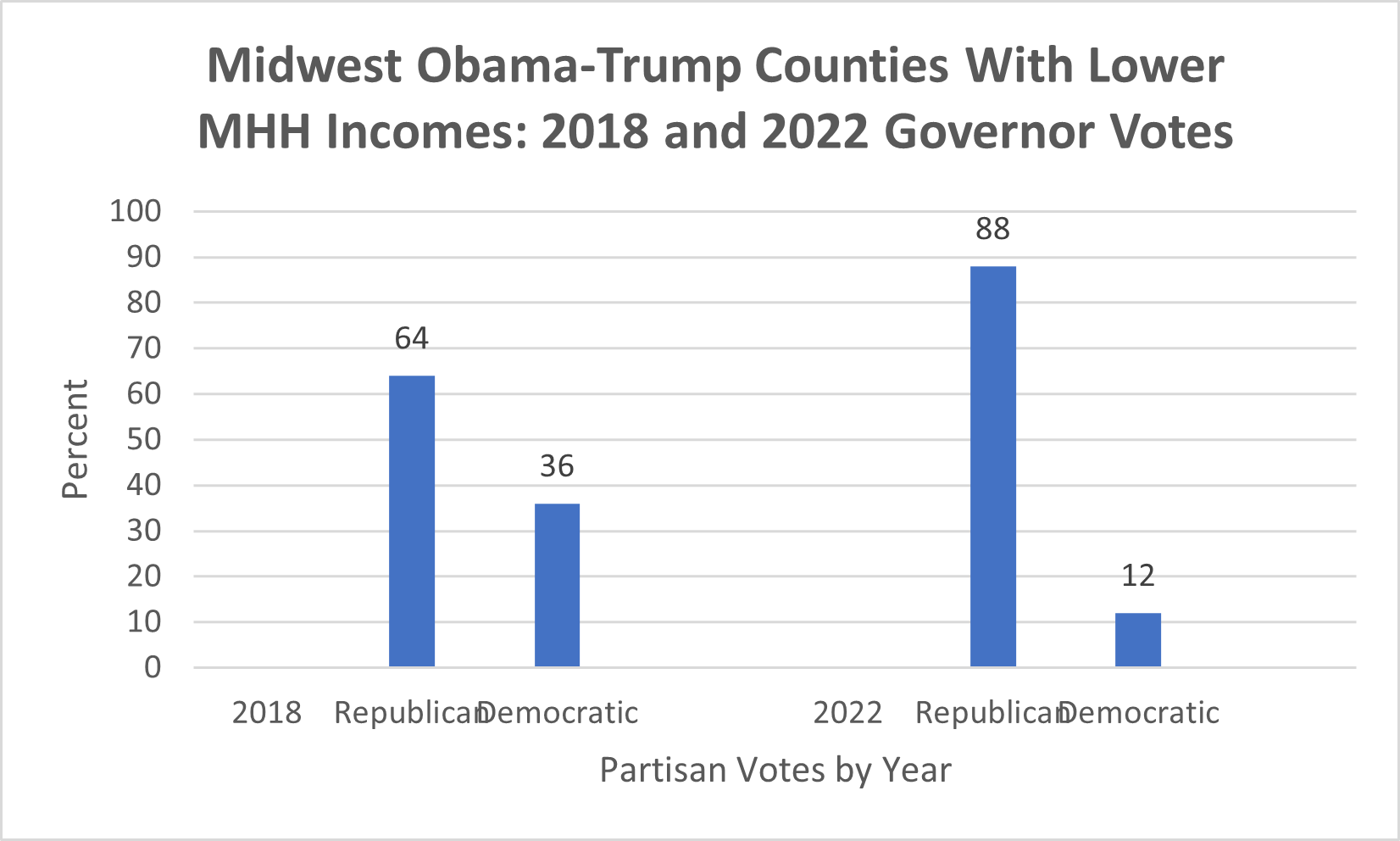

And these declining communities, for the most part, have been moving more and more toward the Republicans during recent election cycles. Figure 2 illustrates the continued loss of working-class voters among Democrats in communities that continue in relative decline, lose population, and see declining household incomes.

Within the 61 percent of counties from Obama to Trump with declining populations:

- Two-thirds (67 percent) voted for Republican candidates in the 2018 election. That number increased to 93 percent of counties voting for Republican candidates in 2022.

And within the 83 percent of counties from Obama to Trump that had incomes below their state median:

- In 2018, 64 percent of these low-income counties voted Republican, but 36 percent still voted Democratic. By 2022 in those same low-income counties, 88 percent voted Republican and only 12 percent voted Democratic.

Additionally, in 2022, Republican gubernatorial candidates improved on their performance from 2018 in 105 of the 113 Obama-Trump Midwest counties.

Across the Midwest, working-class voters in counties that once leaned solidly Democratic and continue to decline have, by and large, shifted their political preferences to the right since the 2016 presidential election. These findings is consistent with other recent survey by American Family Voices work for voters in the “Factory Towns” of six key Midwest battleground states, which found support for Democratic candidates among the region's working-class voters greatly diminished.

With another presidential election looming in 2024, Democrats are trying to repair their standing with working-class voters, in part by providing new jobs and opportunities for residents of industrial areas. of President Biden unprecedented investment in place-based industrial policy—much of it focused on the U.S. Heartland, including last year Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act (IIJA), Chips and Science Actand Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—represent a dynamic effort to win back the blue-collar voters at heart.

This same type of focus on kitchen-table economic issues must also be brought to bear in all of our democracies — from any and all parties. The unprecedented recent place-focused industrial policy Investing in people, innovation and infrastructure in the industrial heartland of the US is good for our economy and democracy—as are similar investments in industrial areas in the UK, Europe and among other allies. Like Andy Westwood of the University of Manchester argued in favor of the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD), “Creating better jobs and supporting businesses and industries in 'industrial hotbeds' not only helps rebuild local economies, reducing discontent among the “geographies of discontent“, it also creates more stable national governments as actors in the global economy and the institutions that govern it.”

Restoring trust and optimism among the residents of the industrial heartlands here and abroad can help heal our polarized politics and make it possible and easier for our collective citizens to unite around the biggest challenges facing democracies, such as Russia's bare-bones aggression and China's increasingly threatening posture on the world stage.