On a sunny afternoon in early June, I ask some Silicon Valley tech workers in downtown Palo Alto what they think of when they think of Nebraska.

“Corn,” says a 26-year-old Python coder in an a16z t-shirt. “Only corn everywhere.”

“Tractor…farms…cows,” says his friend. “And yes, corn.”

In the San Francisco Bay Area—the global mecca for technology, innovation, and venture capital money—the Midwest doesn't seem to love the streets much. Despite all these, This it is where the computer chip was born. There Jobs and Woz built the first Apple machine in a garage and Google was invented in a dorm. Silicon Valley, the axiom says, has an ambition and drive that can't be replicated.

But the change is unexpected: Investors are flocking to Mid-American cities like Omaha and Des Moines. Startups are ditching the California prairies for a little Midwestern mojo. And the “Silicon Prairie” — cornfields and all — is having a moment in the merciless sun.

“I'm just above San Francisco…”

In early 2010, Mark Kvamme, a prominent venture capitalist in Sequoia Capitaltook a 6-month leave of absence and left Silicon Valley to explore the Midwest.

When he was there, something strange happened. “I kind of fell in love with the place.” Kvamme said Forbes. “The opportunity I saw in Ohio and the rest of the Midwestern states … I really felt like something was happening here.”

He hired Chris Olsen, also a VC at Sequoia, and made him a proposition: They would leave California and start their own fund exclusively for Midwest companies.

In 2013, the duo set up shop in Columbus, Ohio, grew a $250 million and began investing voraciously in local talent. It was so successful that they grew more $300 million in 2016.

Kvamme assumes that “90% of the future technology market capitalization will be created outside of Silicon Valley.”

“I think people will look back and say it was so obvious that the Midwest was going to come up because the numbers were so stacked against it,” he says.

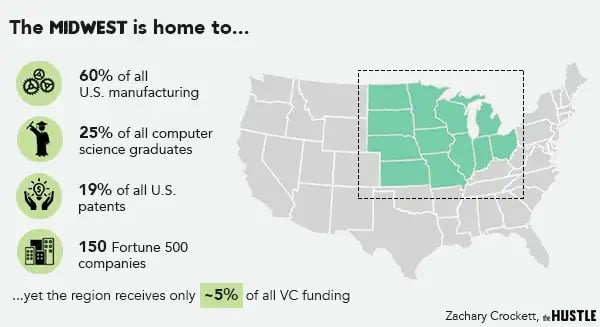

The “numbers” he refers to don't lie: The Midwest is home to 150 Fortune 500 companies, 25% of all US computer science graduates and 60% of the nation's manufacturing base. It's a big market (19% of America's GDP) and full of innovation (19% of all US patents) — yet it accounts for only 5% of all venture capital funding.

In Kvamme's estimation, the Midwest is seriously “underrated.”

A growing number of disaffected Silicon Valley VCs are starting to catch on and are shifting their focus to overlooked Midwestern markets.

Steve Case (co-founder of AOL) and JD Vance (author of the widely read Hillbilly Elegy) was recently releasedRise to the resta $150M Midwest seed fund; supported by Jeff Bezos, Eric Schmidt, Howard Schultz and Ray Dalio.

VC firms and incubators — both homegrown and transplanted — dot the prairies, from Rev1 Ventures to Colombo, yes Cintrifuse in downtown Cincinnati.

And in the so-called “Rust Belt Safaricoastal VCs are flocking to Midwestern cities like South Bend, Indiana by the luxury busload, seeking out local startups for investment opportunities.

“I'm just over San Francisco,” one on safari he said The New York Times, between bites of vegan donuts. “It's so expensive, it's so crowded… It's the worst part of the social network.”

Think Midwest

Traditionally, the vast majority of tech investors (and consequently, the vast majority of startups) have remained entrenched in coastal America. As of 2017, 76% of all venture capital money was channeled alone 3 states: California, New York and Massachusetts.

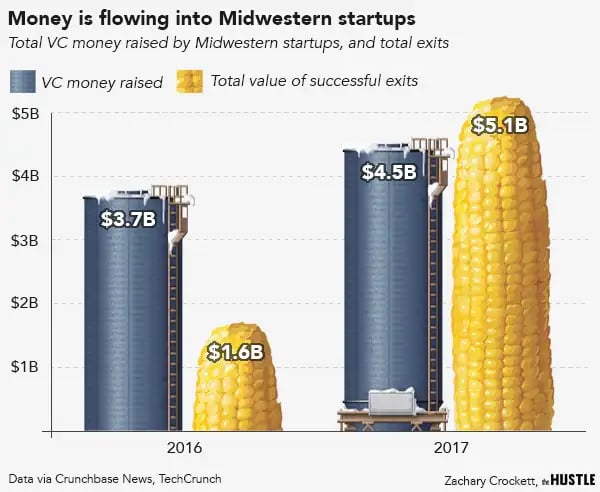

But last year, total investment in Midwestern companies was up to an all-time high of $4.5 billion. And investors are seeing returns: in 2017, 37 companies in the region got out for a total value of $5.1 billion, up from $1.6 billion in 2016. CoverMyMeds, Ohio's “first tech unicorn,” sold for $1.1 billion, good for the largest exit in the state's history.

Among the VCs, the boring companies, the companies that promote businesses are all the rage — and they don't miss the Midwest.

Companies growing in the area are varied and varied, from Omaha-based WordPress hosting platform Flywheel to Wichita-based industrial company Nitrade Solutions. As you might expect, there is a focus on manufacturing and agriculture, but industries span IoT, insurance, education, industrial, healthcare, and motorsports.

In an area in desperate need of growth, this boom is creating thousands of jobs, the majority of which are “medium technology', or tech jobs that don't require a college degree.

Christopher Miller, a 31-year-old who lives in St. Louis, is among the new hires.

After graduating high school, he worked in various retail and construction jobs with an average salary of $22,000 per year. In 2016, he underwent a technical training program and now makes $57k as a network specialist at a mid-sized tech company.

“These opportunities didn't even exist 10 years ago,” he says. “It's pretty surreal to see how much things have changed.”

The mythology of the Midwest's inherent lameness — “It's in the Rust Belt!”? “No innovation there!” “No capital!” “No talent!”? “The rivers are all burning!” – is dying.

Stephanie Luebbe is its executive director Nebraska Angelsa network of 60 angel investors who have invested $11 million in local startups to date.

He clarifies that it is not so much the companies movement in the Midwest, as Midwest startups choose to stay there, rather than relocate to places like San Francisco. In Nebraska, there is more capital for development than the number of companies willing to take it on.

“There are many reasons to invest here or start a company here,” he says. “The dollar goes farther here than it does on the coast, interest rates are higher, there's a ton of available talent and there's the Midwest work ethic.”

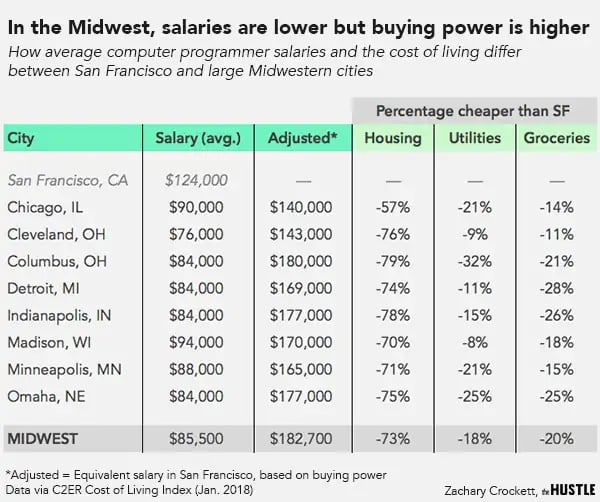

In San Francisco, the average software engineer does $124 thousand (19% higher than the national average), with top talent often earning two or three times as much. In Ohama, the same job pays $84 thousand (19% below average) — but the cost of living it's about a third of what it is in the Bay Area.

“I can live in an apartment that's bigger than a closet, for a quarter of the price,” a developer who recently moved from San Francisco to Ohio tells us. “And my grocery bill is half [what it was].”

There is certainly no shortage of talent to choose from. As Inc. He notes that the Midwest has one of the most important clusters of high-quality universities in the country, with the University of Chicago, Notre Dame, Northwestern, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois and Carnegie Mellon all within an hour's flight.

In San Francisco, much of the capital also goes to things that have nothing to do with innovation. With a lower cost of living, companies in the Midwest enjoy burn rates that are up to 50% lower than Silicon Valley, allowing them to “push to breakeven and profitability” more quickly.

But perhaps the most important benefit of starting a startup in the Midwest is the proximity to the core issues and customers.

“A lot of companies on the coast are trying to solve problems that exist in Middle America,” says Luebbe. “Startups in the Midwest are better prepared to deal with these problems.” He cites an Omaha-based company that creates data analytics for small rural hospitals, the majority of which are located in the Midwest.

The Midwest is NOT the next Silicon Valley

One thing I hear over and over again from entrepreneurs, investors and tech workers in the Midwest is that they don't want to live in the shadow of Silicon Valley.

For years, pundits have declared any place with a burgeoning tech scene the “next Silicon Valley:” Boulder, Jute, DC, Seattle — hell, even Sweden. But these comparisons are exaggerated and take away from the things that make each city unique.

“[There’s a] distinctly Midwestern approach to business,” he says Zach Ferres, a CEO who got his start in the Ohio tech scene. “In that tech community, your word was your bond—anyone who refused a promised handshake was shunned. Successful people helped others learn and grow. The businessmen from the surrounding areas felt like members of a big family.”

The Midwest is special in its own way. Yes, it has corn fields. And a tractor. And its lakes occasionally catch fire. But it has also channeled its culture into a distinct brand of entrepreneurship.

And as they say, the cows come home.