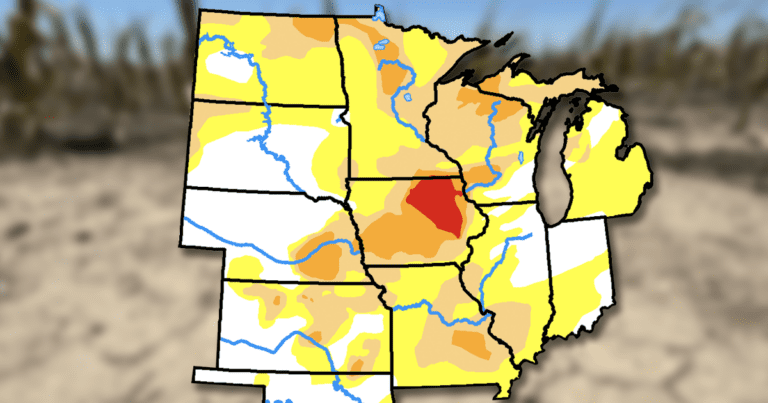

As planting season approaches for farmers across the Midwest, large parts of many states are still in drought.

The latest update from the US Drought Watch shows that the upper Mississippi River from Minnesota to Missouri is in moderate to severe drought, with a portion of northeast Iowa in extreme drought. Some areas of the Midwest have been experiencing drought since mid-2020.

Although winter rains have improved conditions in some parts of the region, the outlook remains challenging for Midwest farmers. While warm temperatures made it easier for the soil to absorb water, it also made it easier for water to evaporate from the soil after snow or rain. Now, drought concerns are starting to emerge across the corn belt, said Dennis Todey, director of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Midwest Climate Hub.

“That way we get hit from both sides,” Todey said. “There's just not enough water returning to the ground and we're already losing it back to the atmosphere. And that just keeps getting worse as the spring goes on.”

Officials from the Army Corps of Engineers and supporting services laid out the long-term issues within the Missouri River watershed in a phone call Thursday. Large parts of the basin have experienced lower than normal rainfall along with higher than normal temperatures.

“It's going to take some time and well above normal precipitation to ever fill those lower, if you will, lower bins or lower soil and groundwater levels in the basin,” said Doug Kluck, director of the Central Region Climate Services. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In addition to the drought, the US just recorded it the warmest winter on record. This was also the case in the Midwest and Great Plains, where Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota and Wisconsin each recorded their warmest winters. Northern parts of the Midwest have been running 12 to 16 degrees above normal for the past month, Todey said.

“The numbers we're dealing with this winter are amazing in terms of temperatures,” he said.

Some of that warmth is due to the El Niño weather pattern, but that's only part of the story. Todey said that while it's hard to link climate change to a single event like this drought, there are signs of climate change in what the Midwest is experiencing now.

“An El Niño winter in the Upper Midwest has a better chance of being warmer than average, and it was,” Todey said. “But we also see a long-term trend driven by climate change in the way it warms winters. So those two fingerprints are over this whole winter.”

As the climate continues to warm, the Midwest will experience an increase in extreme weather events in the Mississippi River Basin, said Jason Nauft, a professor at St. Louis University. This will create challenges for Mississippi-based systems such as agriculture, the economy and energy production.

“We can expect to see more intense droughts and more intense floods,” Knouft said. “In terms of the river and the water cycle, I think that's what we need to prepare for.”

The drought is changing the calculus for some farmers as they decide how to run their businesses.

Bright Hope Family Farm owner Lainey Johnson recently switched to exclusively growing flowers on her farm in southeastern Nebraska, an area currently experiencing moderate to severe drought according to the US Drought Monitor. She made the switch after seeing particularly poor yields for her garlic crop last year, which she attributes to the drought.

“Flowers are more profitable, but they also have much less water needs,” Johnson said. “And so we switched to drip irrigation as much as possible to water less and get water directly where the plants need it. We've kind of broken down a system that makes us more drought-resistant.”

Johnson is president of Women in Local Food and Farming. He said farmers he has connected with who have row crops or pasture for livestock are struggling the most.

“We talk about the drought and how it's affecting our farms and our businesses, and just try to brainstorm and support each other,” Johnson said.

There could be a silver lining for farmers in this ongoing drought. In recent decades, a more common spring complaint was soil that was too wet for planting, Todey said. This dryness could allow farmers to plant earlier than usual.

“This part is not bad,” said Todey. “But we're going to continue to be very dependent on rainfall as we go through the year because we don't have that moisture in the profile.”

This story was created in collaboration with Harvest Public Media, a partnership of public journalism news media in the Midwest. He reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.