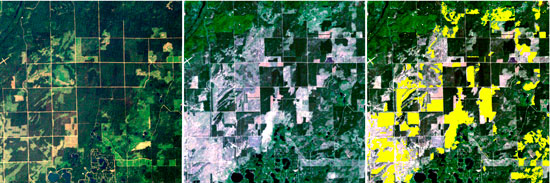

Mutlu Ozdogan, assistant professor of forest and wildlife ecology at UW-Madison, processes images from the Landsat satellite to reveal changes in forest composition over time. Shown in this composite is the dry pine forest of Bayfield and Douglas counties in northwestern Wisconsin in 1989 (left) and 1995 (center). Vegetation appears green in these true color images. A computer algorithm compared the 1989 and 1995 images and identified yellow areas in the right panel as harvests in between. Credit: courtesy of Mutlu Ozdogan

x Shut up

Mutlu Ozdogan, assistant professor of forest and wildlife ecology at UW-Madison, processes images from the Landsat satellite to reveal changes in forest composition over time. Shown in this composite is the dry pine forest of Bayfield and Douglas counties in northwestern Wisconsin in 1989 (left) and 1995 (center). Vegetation appears green in these true color images. A computer algorithm compared the 1989 and 1995 images and identified yellow areas in the right panel as harvests in between. Credit: courtesy of Mutlu Ozdogan

(PhysOrg.com) — Using satellite imagery, Mutlu Ozdogan, assistant professor of forest and wildlife ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is automatically creating maps that show where trees have been harvested in the form of clear areas over five time periods.

By many measures, Wisconsin has the largest forest products industry in the nation, and according to Forward Wisconsin, it is the largest employer in 23 counties, with 72,000 employees and 14 percent of manufacturing jobs.

But tracking what's happening on the ground in terms of the location, shape and size of harvested plots has never been easy, says Ozdogan.

About 30 percent of Wisconsin's forests are publicly owned, and maps are available showing harvest on that land. However, most harvesting is done on private lands, leading to a gap in our knowledge.

Wisconsin's forest covers 16 million acres, Ozdogan says, “and has enormous economic, cultural, ecological and recreational benefits.” Large-scale harvesting, mostly of softwood for paper, leads to fragmentation and changes in forest composition and biodiversity, he says. “Wisconsin is the number one paper-producing state in the nation, and deforestation affects those values in different ways, but the first step to understanding what's happening is to make a map.”

The maps begin with images from NASA's Landsat satellite, which sees the Earth in many different wavelengths of light.

To enable photosynthesis, tree leaves absorb most of the visible red light from the sun, so removing trees greatly increases the reflection of visible red light. Although areas with diseased trees that have fallen from the wind or that have burned can also increase reflectance, these effects can usually be distinguished from tree removal, Ozdogan says. “Most of the harvest is bounded by straight lines, while fires, wind gusts, and disease outbreaks are irregular in shape, so they are often easily distinguished from harvests.”

To confirm accuracy, Ozdogan compared his maps with hand-drawn maps based on the same Landsat imagery. “The human brain is the best image processor in the world,” says Ozdogan, “and I guess these hand-made maps are better than ours, but we're right at least 90 percent of the time.”

Where the computer excels is in productivity. A Landsat pass covers a square about 110 miles on a side, so only three passes can document the situation in the boreal forests of Wisconsin and Michigan's Upper Peninsula. Ozdogan develops a series of maps showing changes at five-year intervals, from 1985 to 2010.

Once the technique is perfected, Ozdogan plans to expand it to the entire forests of North America. “We have the computer resources to do this, and once the algorithm is stabilized, we will move in that direction, mapping the harvest areas, wall-to-wall for the entire country every few years, using free, open-source tools.”

Ozdogan also envisions creating an online platform at UW-Madison “where scientists, non-governmental organizations, policymakers and anyone else interested in this kind of data will be able to come and do the analysis themselves. They will be able to interpret the results. and draw their own conclusions from data that are free from subjectivity.”

Ozdogan adds that the computer-generated maps can be merged with other data sets related to water conservation, insect and disease outbreaks, fire, weather and climate.

The maps will also be useful for exploring how Wisconsin's large herd of deer changes the forest as it finds suitable habitat in typical boreal forest plants and trees. Removing trees creates “edge” habitat — a meeting of fields and forests — that deer prefer, and a better ability to analyze the locations of edge and deer will improve understanding of their relationship, says Donald Waller, a UW-Madison professor of botany. and an expert on deer in the woods of Wisconsin.

“Seeing the extent of forests, openings and edges and their proximity to each other is important because deer and other wildlife respond to edges and openings,” says Waller. “This work is valuable in showing us the true state of our forests — at a landscape scale.”