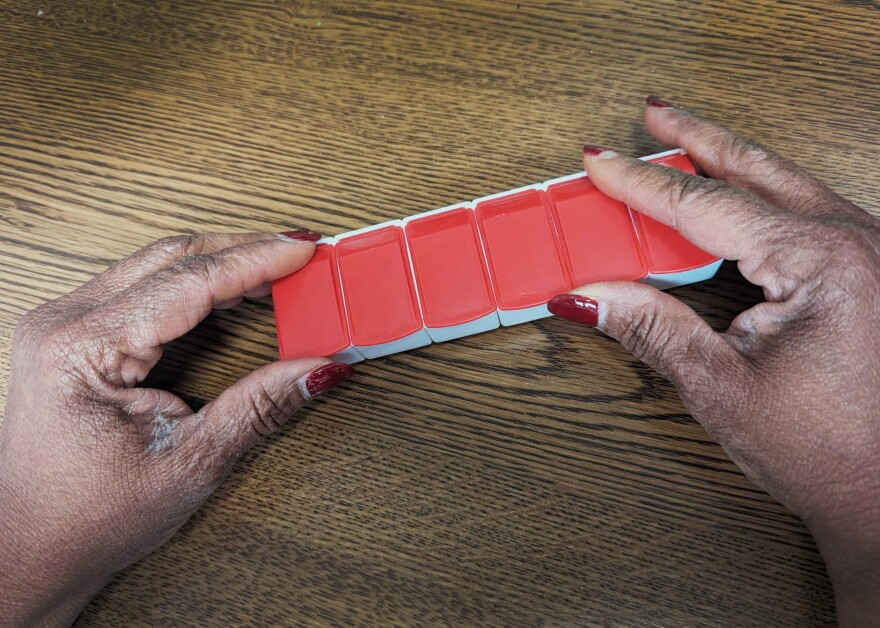

LaTrischa Miles has lived with HIV for nearly three decades. For years, it meant she had to take up to 16 pills a day. Her HIV regimen used to complicate the care she received for other conditions, including diabetes.

It is now under control, he said. Thanks to medical advances, “I take a pill a day for HIV.”

But Miles, a treatment adherence manager at KC CARE Health Center in Kansas City, Missouri, admits her daily routine isn't “one size fits all” for others living with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

“I take my meds in the morning and I'm done,” Miles said. “Not everyone is used to taking medication.”

The healthy balance Miles has created while living with HIV now gives her the opportunity to use life and work as examples to help others affected by the HIV epidemic. And she is not alone.

“Black women are disproportionately affected,” she said. “More so than white or any other race – and for a variety of reasons.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control, Black Americans account for about 40% of new HIV diagnoses in the US

And, according to more CDC data on HIV, about 54% of new diagnoses in the US are black women and girls – making them 17 times more likely to get HIV than their white counterparts.

Percentage of black women living with an HIV diagnosis:

- Iowa: 27.1 times more than white females

- Kansas: 16.5 times more than white females

- Missouri: 12.8 times more than white females

- Nebraska: 16.5 times more than white females

Source: AIDSvu (2021)

Miles attributes the disproportionate infection rates to two main factors: A lack of education about how HIV is contracted and transmitted, and the lingering stigma associated with the virus in the Black community.

“People are hiding or isolated, and that just perpetuates the stigma,” said Miles, who is also the co-chairman of its board of directors. Positive Women Networkdedicated to improving the lives of women and girls living with HIV.

Lawrence Brooks IV

/

KCUR 89.3

“You can't end stigma or fight it if you don't talk about it.”

Miles' personal and professional experience suggests that a major issue in the Black community is the shame women and girls face when talking about HIV, despite the many advances in treatment since the 1980s. And when women don't disclose their situation due to fear of isolation or ostracism, she said, the myth that women are unaffected by the HIV epidemic is unwittingly perpetuated.

“I think people still see it more as a moral issue, as opposed to a human issue,” he said. “I think sometimes people want to blame or point the finger: 'What did he do to deserve HIV?' When in reality no one deserves HIV, just like no one deserves cancer or diabetes.”

Mistrust of the diagnosis

Mary Keyes, a longtime HIV activist in Kansas City who is known in the community by her nickname, “Ms. Anjie,” discovered she had HIV 29 years ago during a visit to her doctor's office.

“He noticed I had swollen lymph nodes,” Keyes said. “He asked me if I had ever been tested for HIV.”

After being tested for “everything in general,” she said, what she learned left her in disbelief.

“When I got there, he told me I tested positive for HIV,” Keyes said. While the doctor was crying, “I was accusing her of doing the wrong test.”

Keyes said her reaction stemmed from a widespread misconception in the Black community about the virus.

“HIV had nothing to do with a black woman,” Keyes said at the time. “It was about 'gays' (and) 'white' (men). So I told her it was wrong.”

In fact, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests over 90% of new diagnoses for black women it results from intercourse with men, the highest rate among all demographics.

Keyes said she contracted HIV after being sexually assaulted and it took years of struggle to fully accept her condition. It's a primary reason he found himself in and out of therapy.

But things changed for Keyes.

“When I committed to staying educated about something I now had to live with one hundred percent,” he said. “I could close the door because I knew how I got it.”

Keyes also faced discrimination in the workplace when people knew about her HIV status.

She said it was other women who came before her who inspired her to stand up and speak her truth.

“I wouldn't be where I am right now if another woman who looked like me didn't stand up and teach me how to be okay and recognize that HIV doesn't define me. And because I have that in my spirit, I can move to help make my community better,” Keyes said.

Lawrence Brooks IV

/

KCUR 89.3

Facing obstacles

Disparities in access to health care are a major issue for black communities across the country, according to reports from the Pew Research Center. A study conducted by the CDC shows that when HIV is added to the equation, Black women and girls face systemic barriers to getting health care.

Keyes said facing those obstacles. it was one of the most difficult aspects of living with HIV.

“I had problems taking medication,” he said. “It kept me from being able to do what I needed to do.

Lack of access to health care can often also limit access to antiretroviral therapyknown as ART, the combination of life-saving drugs used to treat HIV.

In Kansas City, Missouri — where Miles and Keys both live — less than 63 percent of women living with HIV have seen a health care provider and received a viral load test within a month of being diagnosed with HIV, according to with data gathered from AIDSvuan online interactive mapping tool detailing the impact of the HIV epidemic across the US

It's the same story for new drugs like preexposure prophylaxis, commonly known as PrEPwhich is highly effective in fighting HIV infection. CDC data says less than 9% of Black people eligible for PrEP have been prescribed the drug, much less than whites and Latinos.

MHAF

/

US Department of Health and Human Services

Miles said, for many black people, historical mistrust of the health care system plays a major role in keeping people from seeking treatment, as does the way the drug was marketed.

“We've been taken advantage of before, so we tend not to trust it,” he said. “And I think it's some discriminatory practices that have come into play in the way it's been advertised in our community.”

“I think the word still needs to get out in the Black community that this is a preventative measure — the medication they're taking is not going to give them HIV,” Miles said.

To address this mistrust and disparities in HIV health care, the The Biden administration launched the National HIV/AIDS Strategy in 2022.

Kaye Hayes, director of HIV/AIDS Policy for the Department of Health and Human Services, said that because black women and girls are more affected than other racial groups, reaching them is a top goal for the Biden initiative.

To that end, Hayes' department helped develop it I am a work of ART campaign, which helps people living with HIV stay actively engaged in healthcare.

“That's a challenge, you want people to get tested and know their status,” Hayes said. “So to help us in this fight to end HIV, we're talking about HIV prevention.”