A research journal called the Middle West Review published the results for what it describes as “the largest study ever done of who considers themselves Midwestern.” The researchers collected about 11,000 responses.

“The big takeaway is that, indeed, Midwestern identity is very strong,” said study leader Jon Lauck, editor-in-chief of the Middle West Review. “I think there's a general belief that the strongest regional identity in the country is the Southern identity, and that maybe the weakest regional identity is in the Midwest, because the borders are a little more amorphous.”

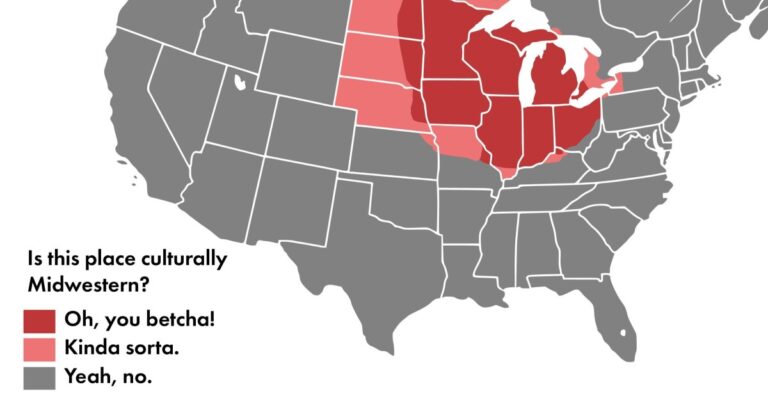

The survey covered 22 states, including 12 defined as Midwest from the US Census Bureau, and 10 on the fringes of what might normally be considered the Midwest.

Lauck decided to include states like West Virginia, Tennessee, and Colorado to determine how far the Midwestern identity stretches.

The Middle West Review

/

Provided

“As I started to organize the research I said, 'Well, this isn't going to be very helpful unless we know what the state next door thinks,' and that's why it's so helpful to have these comparables.”

Residents of Iowa and Minnesota expressed the strongest sense of Midwestern identity, with 97% of respondents in each state identifying as living in the Midwest.

Many Americans would consider Ohio and Michigan strongly Midwestern, but fewer respondents from those states claim the identity. Compare that to Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska, where more than 90% of respondents consider themselves Midwesterners.

Many Oklahomans also identify with the Midwest — 66% in the poll.

“There are skeptics out there who think the Midwest doesn't exist, or it's not a place where people have a strong sense of regional identity,” Lauck said. “And this study clearly overturns both of those claims.”

The Middle West Review is a partner Midwestern History Association and is published by the University of Nebraska Press. The Midwestern Identity Poll survey was conducted by Emerson College.

Why do we need to know this?

The Middle West Review

/

Provided

The poll goes over the number of people in each state who consider themselves Midwestern. The researchers asked a total of 10 questions — covering gender, race and ethnicity, political beliefs, and education level. The full survey results will be available at Middle West Review website in an open source database.

Lauck, who has authored several books on Midwestern history, said the research is important for reasons other than dispelling myths. Researchers from a variety of fields, including history, geography, political science, economics and demography, will find it useful in their work, he said.

In addition to measuring statewide sentiment for the Midwest, the survey provided results from individual zip codes in all 22 states. This means that anyone can study specific communities where people identify most strongly as Midwesterners – and less so.

“Since we have this data by zip code, we can really eliminate it,” Lauck said. “If it was just state-level data, we wouldn't be able to do this. We wouldn't be able to say, “Which is the more midwestern parts of Michigan or Missouri.”

A somewhat surprising takeaway from the research, Lauck said, is that people's sense of the extent of the geography of the Midwest goes farther west than previously thought. For example, 92% of Nebraska poll participants identified as Midwestern, even though much of Nebraska is located in what some refer to as the Great Plains.

“Great Plains identity is probably a lot weaker than we think,” Lauck said. “I mean, how many people do you know who say to themselves, 'Well, I'm just a simple person.' Nobody says that.”

Ness Sandoval, a demographer at St. Louis University, grew up in Scottsbluff – population 15,000 – in the Nebraska area. He strongly identifies as Midwestern, regardless of his birthplace's western location in what some might consider the Great Plains region.

His maternal ancestors left Mexico in 1910 and immigrated first to New Mexico, then to Kansas and finally to Nebraska, finding work in the railroad industry. Midwestern institutions like the University of Nebraska and Creighton University served as symbols of the American dream, Sandoval said.

He points to the trend of “brain drain” in rural communities that both the survey and his census data show.

“There are no stores, a gas station, no fast food,” Sandoval said. “These cities are never coming back. We're going to see more 'small towns,' like my town of Scottsbluff being the big city.”

A sense of place may not be enough to keep Midwesterners in rural areas, but Lauck said Midwesterners may not venture too far.

“There's an increasing number of people staying close to home,” Lauck said. “And the characteristics and traditions of their families.”

Lauck said the desire to identify with an area also exerts a strong pull.

“I think every person has a deeper and natural instinct to want to know who they are and what their identity is, and one of the most critical forms of identity is where you come from,” he said. “I think there's a completely natural and obvious and strong desire to know who you are and how your place has defined you.”

Midwest view

There are there is no shortage of stereotypes and assumptions about the Midwest as a geographic region. A popular X (formerly Twitter) account is called Midwest vs. All plays with the weather, landscape, people, food and culture of the region, to the delight of around half a million fans.

Then there is the literary Midwestern pastoral tradition, which centers rural narratives that celebrate a “mystical as well as practical” attachment to the land. Practitioners of this genre are predominantly white and include novelist Willa Cather (Nebraska), poet James Wright (Ohio), and poet Theodore Roethke (Michigan).

Understanding the region through a narrow lens fails to take into account the diverse lived experiences of the people who inhabit the region, said Ashley Howard, a University of Iowa history professor who studies African Americans in the Midwest.

“In many ways the assumptions people hold about the Midwest come from both inside and outside the region,” said Howard, who had not read the study before being interviewed. “People struggle to reconcile the contributions of different populations, depicting them simply in one place rather than in it, inserting their experiences into existing narratives rather than writing entirely new local histories.”

Howard, who grew up in Nebraska, said Black life in the Midwest is often overlooked as people think about what it means to be Midwestern.

“Being a Black Midwesterner is a complicated identity,” he said. “We are often illegible as our experiences read as authentic to both our white counterparts in the region and those of our race but outside the Midwest.

Just as the Midwestern pastoral celebrates a predominantly white idea of the region, some of the most iconic representations of Black American life come from the Midwest, Howard said. It showed Motown, writers like Toni Morrison and Rita Dove (both from Ohio), the photography of Gordon Parks (Kansas), and the art of Elizabeth Catlett (who spent much of her career in Iowa).

“On a personal level, I think chili and cinnamon rolls are a perfect combination,” Howard said. “And I would never leave the house wearing gloves on a 55-degree day, even though my hands are freezing, because the embarrassment of being seen doing so is too great.”

This story comes from the Midwest Newsroom, an investigative and business journalism partnership between KCUR 89.3, IPR, New Nebraska Public Media, Public Radio St. Louis and NPR.